The very existence of his thesis demonstrates that we are not confined to a McGilchristian cerebral prison indeed, we inhabit a realm woven out of trillions of cognitive, emotional and social hook-ups, as part of a vast community of minds. But it cannot be ignored, because the idea of a viewpoint from which the hemispheres can be judged cannot be accommodated in his hemisphere-centric interpretation of our nature. He mentions this challenge but dismisses it in a manner that seems to mirror the behaviour he ascribes to the left hemisphere. Does he have a third hemisphere from which he can view, and pass judgement on, the other two? Then there is the puzzle of explaining how McGilchrist escaped the tyranny of his own left hemisphere when we are all apparently in thrall to this inner Toad of Toad Hall. Halves of brains are treated as if they were people. One will be obvious from the previous paragraph: McGilchrist’s relentless personification of the hemispheres. All this matters because, McGilchrist believes, the left hemisphere has assumed mastery over the right hemisphere when it should be its obedient servant. The left hemisphere prefers consistency over truth, adopting ‘a reductionist strategy’ to offer us a perspective on the cosmos as ‘meaningless, purely material’. The left hemisphere sees truth as a thing while the right hemisphere sees it as a process. Worse still, it is ignorant of its own ignorance and is less self-critical than the circumspect right hemisphere. Because it constructs devitalised, simplified, thin representations of the world, based on parts rather than wholes, the left hemisphere gets us into all sorts of cognitive and emotional trouble and makes us more likely to be taken in by illusions. As McGilchrist sees it, the attention of the left hemisphere is largely narrow beam and sharply focused, while that of the right hemisphere is wide, sustained and vigilant, connecting with the bigger picture and underpinning emotional and social intelligence.

That book was built around the claim that the two hemispheres of the brain attend differently to what is around us. In pursuit of this aim, McGilchrist offers wide-ranging, indeed world-ranging, investigations ultimately anchored to the arguments he advanced in his earlier book. The purpose of this magnum opus is to ‘convey a way of looking at the world quite different from the one that has largely dominated the West for at least three hundred and fifty years – some would say as long as two thousand years’. Nearly 1,600 pages of text are supported by 2,500 references and thousands of footnotes soliciting the reader’s attention from the margins of the pages.

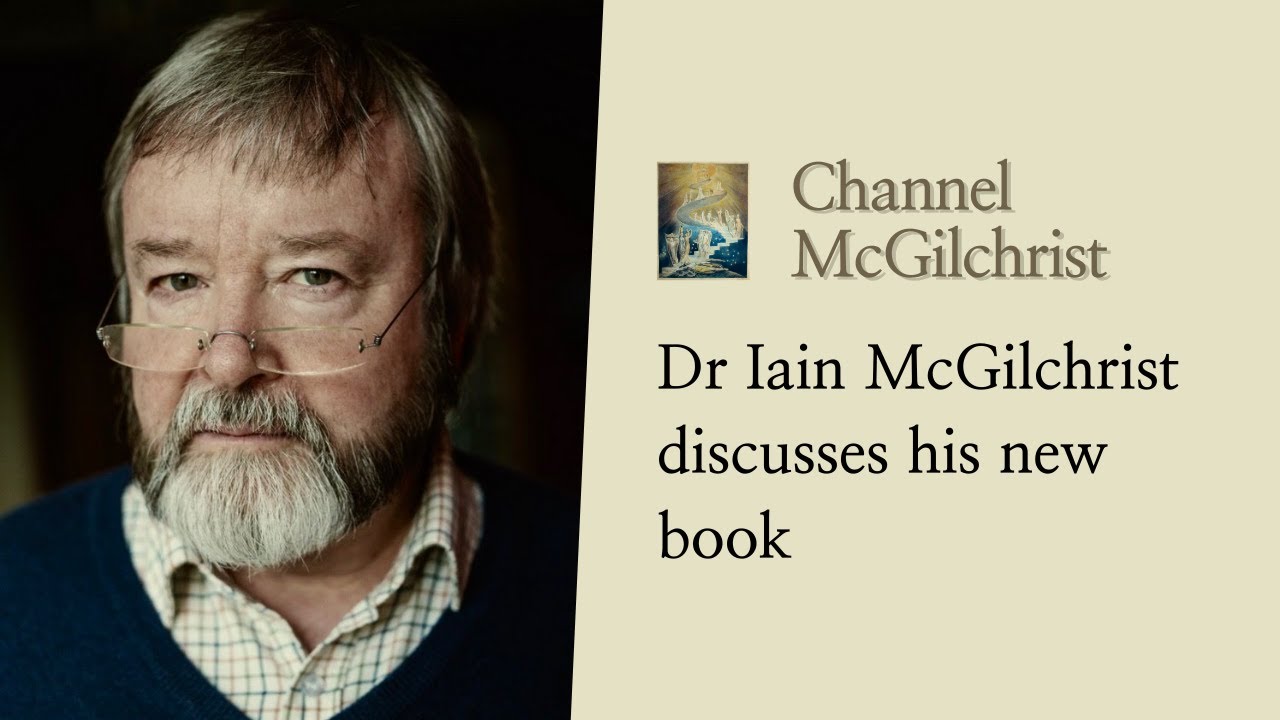

T he sequel to Iain McGilchrist’s much-lauded The Master and His Emissary (2009) occupies two mighty volumes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)